Standing in front of a shop window in the small town of Bad Belzig, on an overcast November day four or five years ago, I realized for the first time my home country is much more connected with the East than I ever imagined. I had come not for the first time from Berlin to the small town in Brandenburg’s Fläming region to visit my friends. But for the first time I was bringing my girlfriend with me, who is from in Kiev in Ukraine. Coming from the train station, we had soon reached the old centre’s paved streets, empty of cars and peopled only by a few Sunday afternoon strollers taking in the renovated facades of the eighteenth and nineteenth century buildings. We stopped in front of a building with a beautiful arch above its door, a former shop on the corner of Straße der Einheit and Sandberger Straße. One of its two windows had been temporarily taken over by the local photographic society for an exhibition. In the other, there were a few photos, but also, inexplicably, sweets in bright wrappers. Most pictures were from present-day Russia, showing factory buildings, others were sepia-toned portraits of Belzig’s famous son: Theodor Ferdinand von Einem. A brief text told his story.

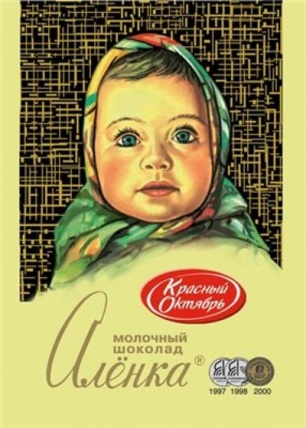

A confectioner and businessman, born in Belzig in 1826, Einem had moved to Russia in 1850 and, the following year, opened a confectionery shop on Arbat street, which was then becoming one of Moscow’s fashionable streets. The business “Einem” (Эйнемъ) thrived, and in 1867 became a chocolate and confectionery factory on the banks of the Moskwa, producing prize-winning confectionery, along with cocoa beverages, cookies, biscuits, gingerbread, glazed fruit and marmalade. After its founder died, in 1876, the company continued to trade under Einem’s name. In 1917, the Bolsheviks nationalized it and, in 1922, re-named it “Red October” (Krasnij Oktyabr, Красный Октябрь), after the revolutionary month. Its products were and still are sold across the countries of the former USSR. In the 2000s, the company was incorporated into a Russian confectionery trust, but its sweets continue to be branded with the “Krasnij Oktyabr” logo.

And we realized, standing in front of that window in the late autumn gloom, that we had in fact some of the sweets displayed in the window in our pockets: “Alyonka” (Алёнка) chocolate bars, with their lozenge-shaped wrappers, showing the picture of a chubby-faced blue-eyed girl in a head-scarf. Bought as small gifts for our hosts from a Russian supermarket in Berlin, they are easily the company’s most famous product. Karina handed one to a little boy, who, with his mum in tow, had sidled up to the window and was wondering aloud about the unusual shape of those sweets, explaining casually to the mother she was “from that part of the world”. The incident stayed with me for a long time, giving me a striking example about the long and deep historical connection my native Germany has with that “part of the world” – Eastern Europe and Russia.

And we realized, standing in front of that window in the late autumn gloom, that we had in fact some of the sweets displayed in the window in our pockets: “Alyonka” (Алёнка) chocolate bars, with their lozenge-shaped wrappers, showing the picture of a chubby-faced blue-eyed girl in a head-scarf. Bought as small gifts for our hosts from a Russian supermarket in Berlin, they are easily the company’s most famous product. Karina handed one to a little boy, who, with his mum in tow, had sidled up to the window and was wondering aloud about the unusual shape of those sweets, explaining casually to the mother she was “from that part of the world”. The incident stayed with me for a long time, giving me a striking example about the long and deep historical connection my native Germany has with that “part of the world” – Eastern Europe and Russia.

Recently, on another overcast autumn day in Cottbus, I felt something similar. We had come for the annual Film Festival and just watched two short films from Belarus in Kammerspiele, Cottbus’ studio theatre. We were walking along Berliner Straße toward the city centre to see a Bulgarian film in the Stadthalle when Karina suddenly said: “I half expect people in the street to speak in Russian, or some other language. I feel like I’m there – in Minsk or one of those films’ locations.” I immediately knew what she meant. We had been immersed in the lives of young people in Belarus, learning about their struggles, taken part in their drama, listened to their dreams and ambitions, and now we were on the windy streets of this unfamiliar East German town. Even though I knew where we were, I was unsure which country we were in – a sense of disorientation had set in. What should have been familiar, at least to me, a native of this country, suddenly revealed itself to be part of that “Eastern Europe” I was hoping to get to know through the films.

The urban landscape held enough cues – the wide swath of road we were walking beside had been cut into the urban fabric by socialist city planners. There were apartment blocks in the distance (we were staying in one near the city’s university). And Cottbus’s other name is Chośebuz in Upper Sorbian, the almost extinct Slavonic language of the area, and we were really on Barlinska droga: all the street signs are bilingual, an added exotic touch.

Incidents like this, and the one earlier, made me realize: I am in Eastern Europe. An area with unclear boundaries, a vast space continuing east – from where I am to Estonia in the north, Croatia and Montenegro in the south, and across the Carpathians and Bulgaria into an undefined distance, perhaps as far east as Azerbaijan, or even further east, to Vladivostok. I had begun to understand it was a complicated place, with many histories and languages, but sharing the common heritage of Socialism and a history of Soviet domination. What I was unprepared for was the realization that, if you are living in Berlin, the Post-Socialist world starts more or less at your doorstep. Somehow I tended to look for it in locales more obviously foreign to me, like Poland, Belarus, Ukraine.

But there was more than that – a deeper realization that imaginary spaces, like ‘the East’, as in Eastern Europe, have no clear boundaries. If you speak about them, they are relative terms. Especially in the case of the large landmass that is Eurasia. When the journalist and author Wolfgang Büscher walked from Berlin to Moscow, people in Poland told him he was leaving Europe, that ‘the East’ started on the other side of the Belarussian border. But the Belarussians made it clear to him they saw themselves as part of the West, too, and that of course it was Russia that was the ‘real’ East. If, in your mind, the East is the home of all that is alien, barbaric or ‘Other’, it necessarily begins further away, across that river, in the next country. But if you are ready to see the connections, if you are ready to connect with it, the mythical elusive East – more a direction than a place – starts anywhere you are, becomes your point of departure.